Living with Food Allergies

What Food Allergy Tests Mean

When trying to determine whether a child has a food allergy, allergy tests can be helpful tools in making a diagnosis.

- Skin rash, itching, hives

- Swelling of the lips, tongue, or throat

- Shortness of breath, trouble breathing, wheezing

- Stomach pain, vomiting, diarrhea

- Feeling like something awful is about to happen

IgE-mediated food allergies have the potential to cause a severe allergic reaction called anaphylaxis [anna-fih-LACK-sis].

There is another type of food allergy called a non-IgE-mediated allergy. With this type of allergy, other parts of the body’s immune system react to a certain food. This reaction causes symptoms but does not involve an IgE antibody.

Examples of non-IgE-mediated food allergies include eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) and food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES).

Doctors usually don’t recommend allergy testing for non-IgE-mediated reactions. Allergy testing is not helpful for diagnosing this type of food allergy.

If you suspect your child has either type of food allergy, it is best to see a board-certified allergist for a diagnosis.

How Are Food Allergies Diagnosed?

To understand different allergy tests, it helps to understand how food allergies are diagnosed.

To diagnose a food allergy, your doctor will ask about your child’s personal and medical history. They will ask for a detailed history of suspected foods, the timing and types of symptoms that occur, and any treatment you have used to help make symptoms better. They will also perform a physical exam.

If the doctor thinks your child may have an IgE-mediated food allergy, they may order allergy testing to help confirm the diagnosis.

What Are the Types of Food Allergy Tests?

The four most common types of allergy tests are:

- Skin prick test

- Specific IgE (sIgE) blood test

- Component test

- Oral food challenge

Skin Prick Test

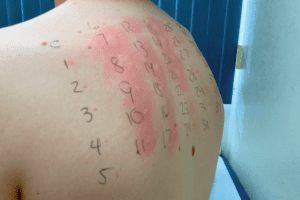

Skin prick testing (SPT) involves placing a drop of allergen onto the surface of the skin and then pricking it to introduce the allergen into the top layer of the skin. It is sometimes called a “scratch test.”

If a specific IgE antibody toward that allergen is present and attached to the allergy cells, then an itchy bump and surrounding redness should develop within 15 minutes. The bump that forms is called a wheal or a flare.

An SPT can have a high negative predictive value (when a test yields a negative result, it is very likely to be correct) but a low positive predictive value (when a test yields a positive result, it is less likely to be correct). This can result in false positive test results. Because of this, it is not a good screening tool, but it is a very reliable test to confirm a history that is consistent with an IgE-mediated food allergy.

In order to get accurate results, your child will need to stop taking all antihistamines for five to seven days before testing.

A common myth is that SPT is not reliable in young infants and children. Actually, SPT for foods is reliable at any age if your child has a history of an IgE-mediated food allergy. Tests may be negative in young children when they are done for other conditions such as non-IgE-mediated formula or food intolerance.

Specific IgE Blood Test

The specific IgE (sIgE) blood test measures levels of specific IgE in the blood for certain foods. This test was previously known as RAST or ImmunoCAP testing.

Like SPT, there is a high chance for negative predictive values but a low positive predictive value. This can result in false positive test results.

Children who have other types of allergic conditions – such as eczema, asthma, and allergic rhinitis – may have higher levels. The values that indicate a possible allergy can differ with every food. But in general, the higher the level, the more likely that your child has an IgE-mediated allergy.

This is a very poor screening test due to the high rates of false positives and meaningless results. The results may come with “class levels.” Class levels are meaningless.

Higher values do not mean your child’s allergy is more severe. There is no test that can determine severity. The results of this test cannot tell you if your child is more likely to have anaphylaxis, a severe allergic reaction. If your child has an IgE-mediated food allergy, they are at risk for anaphylaxis no matter if their results are low or high.

Also, many laboratories will report an arbitrary class level (a created value that is assigned to a result that has no meaning or scientific basis) along with the actual level of specific IgE from the test. This is of no clinical use and does not help determine if your child has a food allergy.

Component Test

A component test is another type of test that measures IgE levels in the blood. It looks at your child’s IgE levels to different proteins (parts or “components”) in a food to help determine what part of the food causes a reaction. Other allergy tests look at reactions to the whole food.

Component testing is often misinterpreted and is best used to determine if tests are elevated due to a true food allergy or if cross-reactivity with inhalant allergens may be causing false positive results. Positive component tests do not necessarily mean your child will or will not have a severe or life-threatening allergic reaction or indicate how much they would need to eat to cause any reaction.

Doctor-Supervised Oral Food Challenge

An oral food challenge (OFC) is a test done in your doctor’s office where an allergist and their staff feed your child increasing amounts of their suspected food allergen. The doctor and staff watch your child very closely for symptoms and are well-prepared to treat symptoms if they occur.

OFCs are considered the gold standard for food allergy testing. They can be considered a good way to tell if your child truly has a food allergy or tell if a previously diagnosed food allergy has gone away.

It is a time-consuming test, but it can be very reliable. Confirming your child’s food allergy (or lack of) can help improve food allergy management and quality of life. Even when symptoms occur during an OFC, valuable information is learned that can help guide management.

Remember, you should never give your child a food challenge at home without your doctor’s permission.

How Accurate Are Food Allergy Tests?

The best test is actually eating the food. With an IgE-mediated allergy, you’re almost always going to know if a certain food makes your child sick. There are no “hidden” food allergies.

With SPT and sIgE blood test, a positive test result for food allergy does not mean your child has a food allergy by itself. These tests are best used to help confirm a possible history for an IgE-mediated food allergy and should not be used as screening tests, at home tests, or large panels.

Are At-Home Food Sensitivity Tests Accurate?

At-home food sensitivity tests are not accurate. They link many vague symptoms to “food sensitivity” to sell you a test kit that is not validated.

Some commercial laboratories offer convenient “screening panels” that claim to test for many different foods. These are rarely used by allergists and immunologists but are more commonly ordered by primary care providers.

Inaccurate results from these types of tests can lead you to restrict your child’s diet unnecessarily. This may then lead to anxiety, family hardship due to food avoidance, and possibly poor nutrition. Poor nutrition can affect your child’s growth and development. It can also delay an accurate diagnosis for any chronic symptoms that may be occurring from other causes.

Other tests such as muscle provocation testing, acupuncture, hair/urine analysis, and applied kinesiology are not validated, standardized, or approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for diagnosing food allergies or intolerances. The American Academy of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology (AAAAI) does not recommend these tests either.